The categories of the "world of atoms" and the "world of bytes", as contemporary economists dub them, split our world into the tangible and intangible worlds. The world of buildings and machinery is thus contrasted with the world of specifications, plans, thoughts and of course software. These categories are not evolving at the same speed. While the tangible world's growth rate is slowing down, the speed of developments in the world of concepts is continuously increasing. Historically, the evolution of the world of atoms has been accelerated by a number of milestones - the invention of writing, the invention of printing, and von Neumann's 1945 plans for a universal computer. Our tangible world has come to contain an ever larger infrastructure, allowing the intangible world to lead its own independent life. But it appears that this is not enough for the intangible world. It is continuously expanding, forcing our tangible world to create a new, improved environment for it. Most recently this was the internet, which has contributed to a further exponential acceleration in the world of bytes in that it has removed geographical distances from the intangible world. What will the next new infrastructure be and what kind of companies will best be able to use it ? Why is there a sobering now in technology-related shares ? What errors has Amazon.com made ?

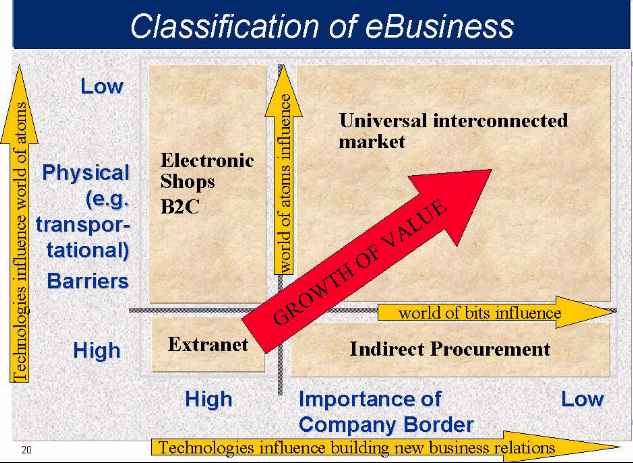

Let's start with a model of electronic commerce, which we will use to try to summarise our present knowledge. Our model has two axes. The horizontal axis is the axis for the intangible part of our world - the world of bytes axis. It is evident that electronic commerce can only bring very limited value when the market is already divided. In such a situation, technology can at most automate the existing business channel and support it in the form of electronic commerce. Against that, as the sector becomes more dispersed, so does the value of electronic commerce. It gives suppliers an opportunity to increase their market shares, while giving customers instant information on other suppliers, pushing prices down.

The vertical axis is our tangible world. This brings into the almost ideal intangible world information on the limitations of our real, physical world. These are primarily transport barriers, but there are also various customs and political obstacles. Electronic commerce can yield the highest value when there are low barriers in the physical world. This is nothing new - electronic commerce has always served us best in services. Internet media, flight ticket sales, and travel services are just three examples of successful electronic commerce today.

As we have already indicated, the world of bytes has supremacy over our real world. Thanks to the great popularity of electronic commerce, our two axes are gradually evolving. We have indicated this development on our graph. On the bytes axis, traditional large companies are breaking up and virtual companies are emerging, consisting of smaller dynamic units. Companies in individual sectors are disintegrating and increasingly adapting to the needs of electronic commerce.

Surprisingly, there are similar developments on the world of atoms axis. Our real world is becoming more and more a world without borders or physical restrictions. In fact, certain physical commodities are gradually becoming virtual, as though it were possible to use intangible media to transport tangible objects. This is not of course possible, but internet entrepreneurs now use the newly emerging infrastructure as though it were - we shall explain shortly. So, while electronic commerce was originally particularly suited to supplying services, its options are increasingly extending to other areas, in this case tangible ones. In consequence, the situation on both axes is changing in favour of a rise in the value of electronic commerce.

Let us now try to say more on these two phenomena - the disintegration of companies into virtual companies and the "virtualisation" of tangible transport. We will start with the second phenomenon. This is nothing other than the growth of the infrastructure of the world of atoms in an effort to support business opportunities in the intangible world of bytes; an inevitable consequence of using this infrastructure is the disintegration of companies as business is broken down into virtual units.

If we look at the relation between the world of bytes and the world of atoms, we find that the world of bytes rules the tangible world. The world of bytes contains within itself plans for e.g. how to run a company or build a factory. The tangible world contains the mechanisms to implement those plans (e.g. using workers, staff, information systems, etc.). In this respect our civilisation is like a living being. An animal's intangible world is its mental processes, which influence all of its behaviour. And just as an animal creates tools to implement its thoughts (hammer, pen, computer), our civilisation creates automatic tools to implement the needs of the world of bytes (e.g. the needs of electronic commerce). An infrastructure is therefore emerging to convert plans and concepts into matter automatically. This process will gradually lead to the virtualisation of matter, separating products' form, function and specification from their physical matter, e.g. wood or metal. This has been precisely the case with information, which no longer requires paper to be conveyed. Thanks to this separation of specification and matter, it will be possible to transport products (i.e. their specification) in a manner similar to that in which intangible information is transported. The product will therefore become virtual, it can travel on communications networks and become tangible (be manufactured) at the moment it is required (when there is a customer for it), wherever we want (where the customer requires). This will lead to classic companies breaking up into companies specialising in individual elements of the customer service process, and will in consequence increase competition along value chain. This will be the next industrial revolution.

An infrastructure is now emerging in the tangible world which can emulate certain functions of the tangible world in the world of bytes, especially transport. The internet can emulate transport for services - which is why certain services can now be offered globally, why there are global companies such as Amazon.com, and why the popularity of their brands is increasing rapidly. The next step in these developments will be the emulation of transport for certain tangible categories.

Science fiction writers have dreamt of creating a machine which could transport not just information, but also matter. According to those authors, we would step into such a machine, which would then analyse us, destroy us, and build an exact copy of us somewhere else. To be honest, that idea doesn't particularly appeal to me. Travelling by plane is not much slower and the likelihood of our physical destruction is somewhat lower than 100%.

In the world of inanimate matter, the idea of separating matter from information is not so drastic. We are already in a situation where physical distances for transmitting information have entirely disappeared, i.e. in the world of bytes,. We no longer need reams of paper to transport information, we don't have to send a celluloid strip by train to transport a film, we don't need to send a magnetic cassette by plane to transport a television programme. Let's now imagine that an infrastructure is created in our world of atoms which would allow us to eliminate distances (and therefore transport, loading and storage costs, and the time required for transport) for a certain area (commodity) in the world of atoms.

This idea is by no means unrealistic. There are already areas in the tangible world where the infrastructure simulates the removal of distances. Perhaps you recall Fleurop, a world-wide network of florists, in which I can e.g. request in Prague that flowers are delivered to an address in New York the same day. Faxes were sufficient for this application. There was no need for more sophisticated means of communication because the flowers are not of course produced on location - I do not therefore need to send a detailed specification of them. But I have to trust the company to make the delivery as ordered. Fleurop therefore uses its brand to guarantee quality. As we shall see shortly, it is again similar to virtual companies in this respect.

Unlike faxes, the internet can extend the option of wireless transport to categories where a detailed specification has to be transported. The internet can therefore transport unique goods, made to measure for individual customers.

We can demonstrate this using book printing as an example. There are now machines on the market for small print runs, which can print an entire book, including the binding, while you wait. There is no need to print more than one book - the price per book is the same for one or one hundred books. While the costs of printing a paperback in a large print run are e.g. 50 koruna, the costs printing it in a small print run tend to run to multiples of that figure, let's say 150 koruna. While this figure is much higher than for the large print run, a small print run is still profitable when the price per book is around 200 koruna. If we take into account the fact that we can print the book directly where we need it, the moment we have a customer for it, our view of the company's economics suddenly change: when printing one book at a time, there are no costs for handling the printed books, or storing them, or transporting them, nor is there the danger of an incorrect estimate for the print run. No books are produced which I cannot sell. Moreover, the customer can choose a title from any publishing company in the world and does not have to wait for delivery - such "books" are transported at the speed of light. The technology is now in place for books to be transmitted in this way - e.g. in pdf format - and presses to print one book at a time already exist. If this system is used on a large scale, small print runs will become even cheaper. The outcome will be that the traditional printing of books in large print runs, their physical storage and costly transport, will not be able to compete with the new way of "virtualising matter", and will disappear. Instead of traditional bookshops, our streets will feature a network of small-scale printing houses. The customer will be able to order a book from home and pick it up an hour later at the corner shop. Alternatively, he can choose a book at the shop, which will then print it while he waits.

The end result is of course nothing less than the disappearance of distribution distances for the entire publishing industry. The customer can order any book in the world. Regardless of whether the book comes from a publisher in Prague or New Zealand, it will be available in a matter of minutes.

For the first time in the history of human civilisation, the elimination of borders has been extended from the world of bytes to the world of atoms. And this is no science fiction. Just as the internet infrastructure has simulated the elimination of borders in the intangible world, today that infrastructure has been extended to simulate the disappearance of borders for the first commodity in the tangible world, involving moreover the transport of fully specified and customised products.

It all starts then with books, but they won't be the only ones. In the not too distant future, other commodities in our tangible world will also be "virtualised".

Let's take furniture as an example. I can easily imagine that just as there are small printing presses, fully automated manufacturing plants for wood and metal parts will begin to appear in various parts of the world. Everyone has probably bought unit furniture at one time or another. And everyone has probably wrung their hands over what was delivered: a number of boxes with planks of various shapes and sizes, a set of screws and printed instructions. There was of course the option of ordering an assembly service to make furniture out of this kit, but if we didn't take this option, we had to do it ourselves.

Let's now look at the supply of unit furniture in purely technical terms: it is clear that essentially all the concepts needed to produce furniture can today be easily transported, basically free of charge. I forward individual parts as CAD plans and send the instructions, e.g. in pdf format. Provided there is an automated manufacturing plant at the other end, where they print the instructions, turn out the parts from materials with the required parameters and put them all into boxes, I have virtualised the entire process of transporting unit furniture. I can, but do not have to, order a team to assemble it - as is the case today.

In other words, furniture has dematerialised in a way not unlike that in which information did earlier. With new developments in technology, the number of such dematerialised commodities from our world of atoms will rise. Along with this, the significance of transport and transport barriers will diminish for an increasing number of sectors.

This trend has important commercial implications. Today's classic furniture manufacturer is a company which covers the entire manufacturing process, from design to production. However, the emergence of the new infrastructure will allow the world of bytes (furniture design) to be completely separated from the world of atoms (physical production). This will be reflected in the world of furniture companies, which will also be split up along those lines. The brand owner will only produce the design. For example, we will select a Korona brand kitchen (the name is fictitious) from the parts on offer in line with our needs. We then specify where in the world we want the kitchen to be delivered. The brand owner will also be the owner of the virtual company Korona, and will therefore act as "orchestrator" - he must put together a virtual company for each supply, which will cover the entire customer service process. In our example, the brand owner will place an order at an automated manufacturing plant in our town and will send it all the information required electronically. The owner is of course responsible for the quality of the end result; if my Korona is poorly produced, I will slander the brand and never buy it again, which naturally harms the brand owner. Ownership of the brand is the greatest value which the owner of a virtual company has (the virtual company does not physically belong to him - he merely rents its individual parts on an order-by-order basis). In other words, the brand owner must oversee all the processes in his virtual company, i.e. oversee their efficiency (wherein lies the benefit of electronic commerce) and overall quality.

Like the publishing industry, the furniture industry will therefore split into a design part, which also own brands, and a general manufacturing infrastructure, with no ownership ties to the design part. Specialised manufacturing companies will be set up, capably of automatically producing individual orders while adhering to strictly defined quality requirements. It is highly likely that those latter companies will also join together and create their own brands, so there will be two or three competing global units, which will be capable of manufacturing and delivering the goods in question at the same quality anywhere in the world. These global brands of "local manufacturers" will compete for orders from the virtual furniture companies. Because static companies will break up into virtual companies, which with their competing sub-contractors will be much more dynamic, the new arrangement will be substantially more efficient. This is why electronic commerce is inherently more efficient than classic business.

This disintegration only applies to those sectors where matter can be virtualised. As we will now show, while the disintegration of companies is a consequence of this process, it is not limited to those sectors. Previously, it was recommended that companies integrate their value chains. They were told to link up with the market as closely as possible, to take charge of supply to the market. Nowadays it is possible to disintegrate an entire value chain, i.e. design, sale, production, logistics and delivery, with no loss of control, to take it away from the company and put it in the hands of sub-contractors. This disintegration is facilitated by the greater transparency of the entire process. The fact that the new communications technologies allow the originally external process to be kept under control, regardless of whether that process is part of our company or not, means that those technologies give us the option of separating supply from the actual production process.

The new technology therefore facilitates the break-up of the value chain. Each part can be performed by whichever company can do so the most efficiently, without the brand owner losing control over the entire process. This puts the brand owner in the role of "orchestrator" - he brings his virtual company together and is responsible for the quality of its products and the optimal functioning of its individual parts. This can be done regardless of which commodity we operate in.

As we said above, in certain commodities the technologies allow much more - they allow matter to be "virtualised", ruling out the need for physical transport. Supply is then directly tied to production. It will gradually be possible for more and more tangible goods to be translated into intangible services, i.e. into the area in which electronic commerce can yield the highest value. In our model these sectors then move to its upper part. As there are more and more "virtualisable" commodities, an increasingly large part of the tangible world will switch to intangible transport, and the value of electronic commerce will rise significantly. This is how the world of bytes influences our tangible world.

We have already said that the main value a virtual company owns is its brand. That is the only thing which really distinguishes it from the competition. The communications environment, i.e. the internet, is shared, as are the cooperating companies which actually serve the virtual company's customers.

Amazon.com has recently made a number of acquisitions, a step which seems to indicate that it is trying to gain and use the advantages enjoyed by classic large companies. Jeff Bezos, Amazon's founder and CEO, argues along similar lines to justify that step. But we have shown that the advantages of large companies do not exist for virtual companies. On the contrary, virtual companies have means quite other than their physical size to achieve higher turnover and accumulate funds for their operations.

Amazon is a typical virtual company, but with its acquisitions it has adopted the tactics of a classic company. In buying electronic shops with a different product range, Amazon is moreover diversifying its operations, and therefore its brand too. Its brand is therefore losing its original content and the strength of its differentiation from the competition.

A side effect of this diversification is that Amazon going into areas which offer a substantially lower gross margin than books. This is putting it further in the red.

The main reason Bezos gives in defence of his diversification strategy is the opportunity of using his existing customer base, offering existing customers additional goods and services. This reason however contains an implicit assumption: that the existing customer base contains potential customers for those additional services. That is in itself a question. For example, while readers of professional literature may be interested in consumer electronics, they will be less interested in toys, and for me a question mark hangs over kitchens (since May 2) and furniture (since May 19). If we look at the situation in terms of the logistics required, it appears even worse. While books are a relatively unproblematic commodity (even though some of Amazon's customers prefer to have goods delivered to the European Union, for customs reasons), there are substantially higher customs barriers for e.g. consumer electronics. With furniture there are also physical barriers - for reasons of price, I will hardly have furniture sent from the United States, even if furniture is cheaper in the United States than here. The virtual transport of furniture, as we outlined so appealingly earlier, is still a mere fiction today. Until that fiction becomes fact, it is necessary to distinguish carefully between the tangible and intangible parts of business. A company which does not carry out this analysis may come to a bad end, regardless of its current popularity. Amazon is moving to the lower part of our model, with high transport barriers and low value added.

Every sale consists of providing intangible services (which Amazon does well) and the need to deliver the service (Amazon needs to outsource that part). It is a parallel to our worlds of bytes and atoms. Some commodities can easily be offered globally, while others are so beset by the barriers of our real world that their global supply does not (yet) make sense. Today the supply of goods whose delivery involves physical barriers costs an entrepreneur money which is not offset by a corresponding rise in turnover. It also costs him something much more important: the significance of his company's brand declines.

No virtual company can afford to jeopardise its brand. That is its only property. It does not share only the other companies in its value chain. It shares its customers too.